Efficient Estimation of Word Representations in Vector Space-2013

1. Abstract

We propose two novel model architectures for computing continuous vector representations of words from very large data sets. The quality of these representations is measured in a word similarity task, and the results are compared to the previ- ously best performing techniques based on different types of neural networks. We observe large improvements in accuracy at much lower computational cost, i.e. it takes less than a day to learn high quality word vectors from a 1.6 billion words data set. Furthermore, we show that these vectors provide state-of-the-art perfor- mance on our test set for measuring syntactic and semantic word similarities..

This paper introduces innovative model architectures that diverge from traditional N-gram models in statistical language modeling, offering a fresh approach to comprehend relationships within a vocabulary. These models prioritize computational efficiency while maintaining high accuracy in representing word semantics and syntactic relationships, showcasing a significant advancement in natural language processing.

1.1 Goals of the Paper

The main goal of this paper is to introduce techniques that can be used for learning high-quality word vectors from huge data sets with billions of words, and with millions of words in the vocabulary.We use recently proposed techniques for measuring the quality of the resulting vector representa- tions, with the expectation that not only will similar words tend to be close to each other, but that words can have multiple degrees of similarity.

2. Model Architectures

In this paper, we focus on distributed representations of words learned by neural networks, as it was previously shown that they perform significantly better than LSA for preserving linear regularities among words [20, 31]; LDA moreover becomes computationally very expensive on large data sets.

The training complexity for the models is given by:

\[O = E \times T \times Q\]where ( O ) represents the overall training complexity, ( E ) is the number of training epochs, ( T ) denotes the number of words in the training set, and ( Q ) is a model-specific factor.

Models are trained using stochastic gradient descent and backpropagation.

2.1 Feedforward Neural Net Language Model (NNLM)

The Feedforward Neural Network Language Model (NNLM) is structured with several layers: input, projection, hidden, and output.

Input Layer

At the input layer, the model considers ( N ) previous words. These words are encoded using 1-of-( V ) coding, where ( V ) represents the size of the vocabulary.

self.embeddings = nn.Embedding(vocab_size, embedding_dim)

Projection Layer

The encoded input is then mapped to a projection layer ( P ) with dimensionality ( N \times D ), using a shared projection matrix. This step is computationally efficient since only ( N ) inputs are active simultaneously.

Hidden Layer

The architecture’s complexity increases between the projection and hidden layers due to the dense nature of projection layer values. For a typical choice of ( N = 10 ), the projection layer size (( P )) ranges from 500 to 2000, while the hidden layer (( H )) usually comprises 500 to 1000 units.

self.linear1 = nn.Linear(context_size * embedding_dim, hidden_dim)

Output Layer

The hidden layer is essential for computing the probability distribution over the vocabulary words, resulting in an output layer with dimensionality ( V ). The computational complexity per training example can be expressed as:

self.linear2 = nn.Linear(hidden_dim, vocab_size)

In this equation, ( H \times V ) is the dominant term. However, to mitigate this complexity, several practical solutions have been proposed. These include using hierarchical versions of the softmax or employing models that

vocab_size = 1000

embedding_dim = 100

hidden_dim = 128

context_size = 3

# NNLM Model Structure

NNLM(

(embeddings): Embedding(1000, 100) // 100,000 parameters

(linear1): Linear(in_features=300, out_features=128, bias=True) // 38,528 parameters

(linear2): Linear(in_features=128, out_features=1000, bias=True) // 129,000 parameters

)

vocab_size = 1000000

embedding_dim = 100

hidden_dim = 128

context_size = 3

# NNLM Model Structure with Larger Vocabulary

NNLM(

(embeddings): Embedding(1000000, 100) // 100,000,000 parameters

(linear1): Linear(in_features=300, out_features=128, bias=True) // 38,528 parameters

(linear2): Linear(in_features=128, out_features=1000000, bias=True) // 128,999,872 parameters

)

Hierarchical Softmax

The model utilize hierarchical softmax, where the vocabulary is represented as a Huffman binary tree. This approach capitalizes on the observation that word frequency effectively determines classes in neural net language models. Huffman trees assign shorter binary codes to more frequent words, reducing the number of output units needing evaluation. While a balanced binary tree would require evaluating \(( \log_2(V) )\) outputs, a Huffman tree-based hierarchical softmax needs only about \(( \log_2( ext{Unigram perplexity}(V)) )\). This results in a significant speedup, especially beneficial when the vocabulary size is large, such as one million words.

2.2 Recurrent Neural Net Language Model (RNNLM)

Recurrent neural network based language model has been proposed to overcome certain limitations of the feedforward NNLM, such as the need to specify the context length (the order of the model N ), and because theoretically RNNs can efficiently represent more complex patterns than the shallow neural networks [15, 2]. The RNN model does not have a projection layer; only input, hidden and output layer. What is special for this type of model is the recurrent matrix that connects hidden layer to itself, using time-delayed connections. This allows the recurrent model to form some kind of short term memory, as information from the past can be represented by the hidden layer state that gets updated based on the current input and the state of the hidden layer in the previous time step.

The complexity per training example of the RNN model is given by:

\[Q = H \times H + H \times V\]where the word representations \(( D )\) have the same dimensionality as the hidden layer \(( H )\). Again, the term \(( H \times V )\) can be efficiently reduced to \(( H \times \log_2(V) )\) by using hierarchical softmax. Most of the complexity then comes from \(( H \times H )\).

RNNLM(

(rnn): RNN(input_size=10000, hidden_size=128) // 1296640 parameters

(linear): Linear(in_features=128, out_features=10000, bias=True) // 1290000 parameters

)

3. New Log-linear Models

In this section, we propose two new model architectures for learning distributed representations of words that try to minimize computational complexity. The main observation from the previous section was that most of the complexity is caused by the non-linear hidden layer in the model. While this is what makes neural networks so attractive, we decided to explore simpler models that might not be able to represent the data as precisely as neural networks, but can possibly be trained on much more data efficiently.

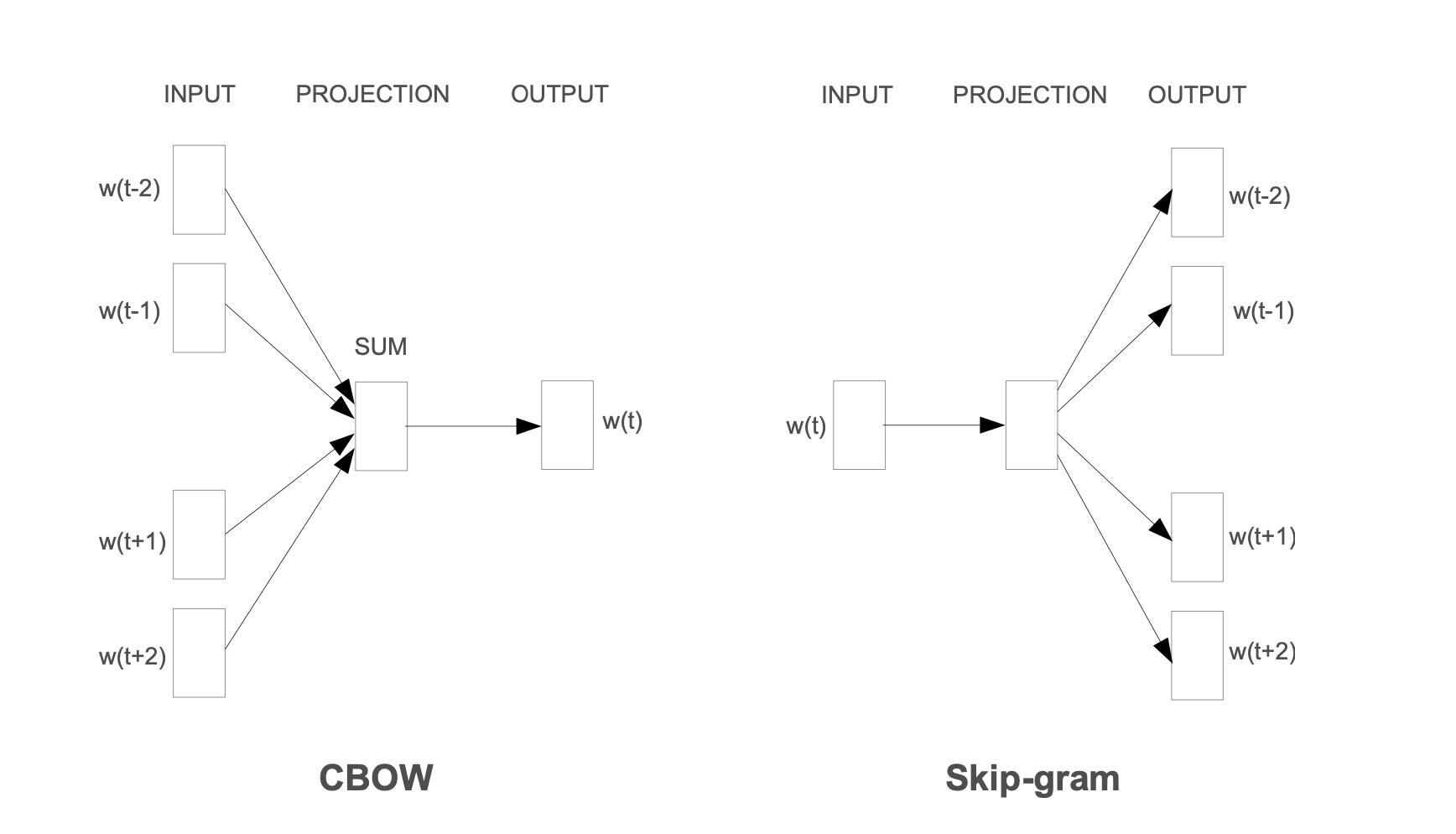

3.1 Continuous Bag-of-Words Model

The first proposed architecture is similar to the feedforward NNLM, where the non-linear hidden layer is removed and the projection layer is shared for all words (not just the projection matrix); thus, all words get projected into the same position (their vectors are averaged). We call this archi- tecture a bag-of-words model as the order of words in the history does not influence the projection. Furthermore, we also use words from the future; we have obtained the best performance on the task introduced in the next section by building a log-linear classifier with four future and four history words at the input, where the training criterion is to correctly classify the current (middle) word.

The training complexity of the CBOW model is captured by the formula:

\[Q = N \times D + D \times \log_2(V)\]Here, ( Q ) is the training complexity, ( N ) is the number of context words (both past and future), ( D ) is the size of the word embeddings, and ( V ) is the vocabulary size. This model is denoted as CBOW, distinguishing it from traditional bag-of-words models by its use of continuous distributed representations for context.

Note that the weight matrix between the input and the projection layer is shared for all word positions in the same way as in the NNLM.

3.2 Continuous Skip-gram Model

The second architecture is similar to CBOW, but instead of predicting the current word based on the context, it tries to maximize classification of a word based on another word in the same sentence. More precisely, we use each current word as an input to a log-linear classifier with continuous projection layer, and predict words within a certain range before and after the current word. We found that increasing the range improves quality of the resulting word vectors, but it also increases the computational complexity. Since the more distant words are usually less related to the current word than those close to it, we give less weight to the distant words by sampling less from those words in our training examples.

The training complexity for the Skip-gram model is given by:

\[Q = C \times (D + D \times \log_2(V))\]Here, ( Q ) denotes the training complexity, ( C ) represents the context window size, ( D ) is the dimensionality of the word embeddings, and ( V ) is the vocabulary size. The model effectively performs classifications for each word, using both preceding and following words within the context window as positive examples, with distant words weighted less significantly.

4. Results and Observations

We found that when we train high dimensional word vectors on a large amount of data, the resulting vectors can be used to answer very subtle semantic relationships between words, such as a city and the country it belongs to, e.g. France is to Paris as Germany is to Berlin. Word vectors with such semantic relationships could be used to improve many existing NLP applications, such as machine translation, information retrieval and question answering systems, and may enable other future applications yet to be invented..

Through algebraic operations on word vectors, we can uncover relationships and analogies, bringing a new dimension to understanding language semantics. The method is simple: subtract the vector representing one concept from another, then add a third, and search for the nearest word vector to this result. For instance, to find a word related to ‘small’ in the same way ‘biggest’ is related to ‘big’, we compute:

\[\text{vector(smallest)} \approx \text{vector(biggest)} - \text{vector(big)} + \text{vector(small)}\]This computation, when applied to well-trained word vectors, often yields the correct association.

5. Comparative Analysis of Model Architectures

A comparative study of various word vector models shows that simpler architectures like CBOW and Skip-gram can surpass more complex neural networks in both syntactic and semantic tasks, underscoring the potential of log-linear models in processing vast datasets.

Comparative performance of word vector models on semantic and syntactic accuracy:

| Model Architecture | Semantic Accuracy (%) | Syntactic Accuracy (%) |

|---|---|---|

| RNNLM | 9 | 36 |

| NNLM | 23 | 53 |

| CBOW | 24 | 64 |

| Skip-gram | 55 | 59 |

The Skip-gram model, in particular, shines in its ability to understand semantic relationships, outperforming other models. This is a testament to the potential of these simpler models in handling large-scale data effectively

Conclusion

In this paper we studied the quality of vector representations of words derived by various models on a collection of syntactic and semantic language tasks. We observed that it is possible to train high quality word vectors using very simple model architectures, compared to the popular neural network models (both feedforward and recurrent). Because of the much lower computational complexity, it is possible to compute very accurate high dimensional word vectors from a much larger data set..

Citation

Mikolov, T., Chen, K., Corrado, G., & Dean, J. (2013). Efficient Estimation of Word Representations in Vector Space. arXiv preprint arXiv:1301.3781.

Date: January 21, 2024