Analytical Exploration of Riemann Surfaces

This introduction explores the application of complex analysis on Riemann surfaces, focusing on defining neighborhoods and understanding the properties of functions, coordinate charts translation maps, providing a foundation for extending complex analytical methods to Riemann surfaces.

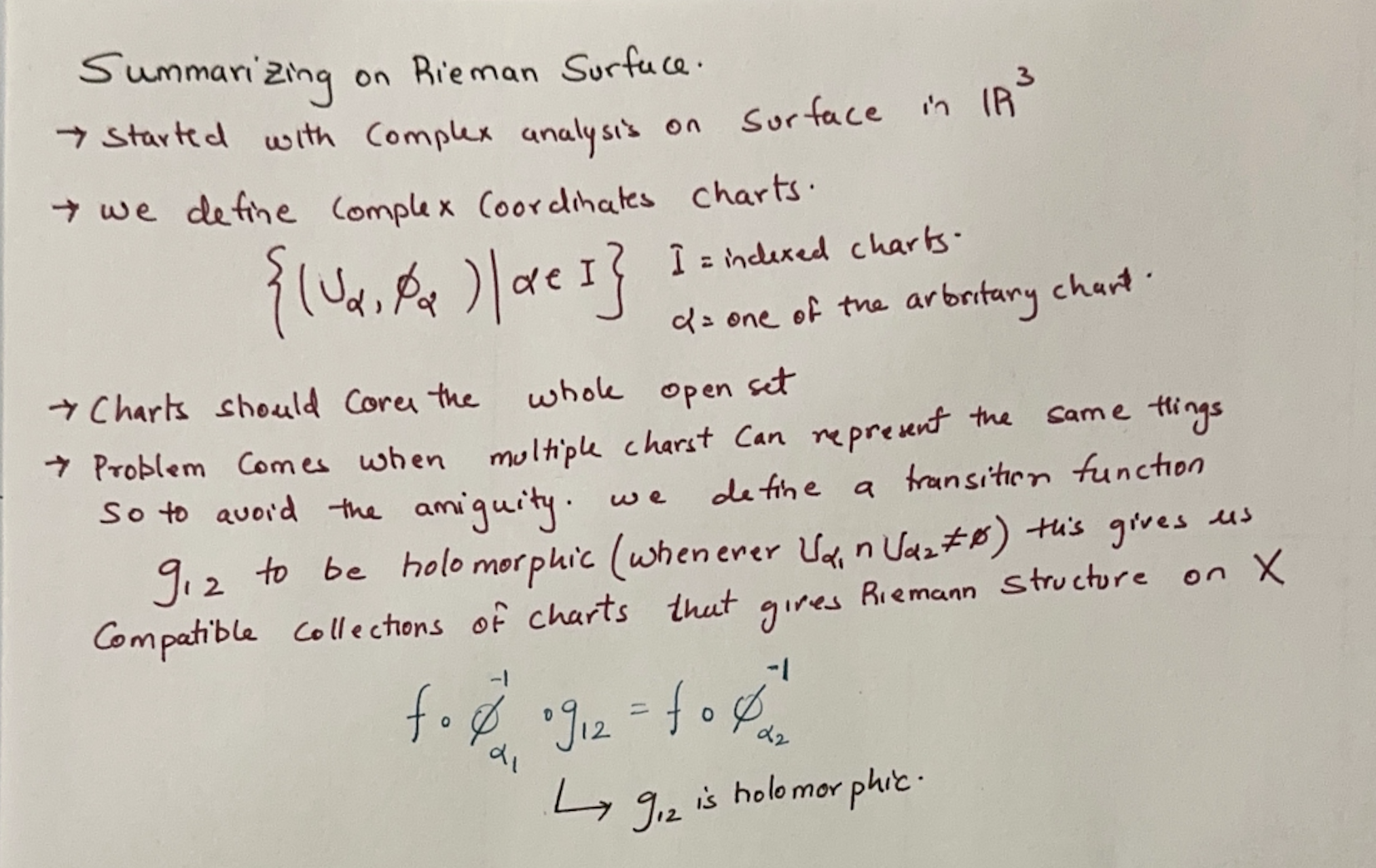

Overview

Riemann surfaces are complex one-dimensional manifolds pivotal in complex analysis, providing a natural domain for defining and studying holomorphic functions that transcend the simple complex plane. These surfaces are essential in connecting diverse mathematical disciplines, such as topology, geometry, and complex analysis, and serve as a platform for multi-valued function integration.

Broader Perspectives

Riemann surfaces play a crucial role in topology and projective geometry. In topology, they clarify the properties of surfaces, linking abstract mathematical theories with more concrete geometric forms. Projective geometry views these surfaces within projective spaces, exploring their symmetries and geometric properties. Additionally, geometric algebra provides a framework to analyze their deeper algebraic structures, enhancing our understanding of their complex interactions.

Focus of This Blog

This blog concentrates on the complex analysis of Riemann surfaces, specifically how they aid in understanding holomorphic functions. We leverage foundational complex variable theories while recognizing that projective geometry and geometric algebra offer valuable insights into their broader mathematical context.

Foundations of Holomorphy

To understand Riemann surfaces, we recall the essential characteristics of holomorphic functions:

A function \(( f(z) )\) is said to be holomorphic at a point \(( z_0 )\) if it satisfies the following conditions:

-

Complex Differentiability:

- \(( f )\) is differentiable at \(( z_0 )\), and the derivative \(( f'(z_0) )\) exists.

- The limit \((\lim_{z \to z_0} \frac{f(z) - f(z_0)}{z - z_0})\) exists.

-

Analyticity: \(( f )\) can be represented by a convergent power series in the neighborhood of \(( z_0 )\):

\[f(z) = \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} a_n (z - z_0)^n\] -

Cauchy-Riemann Equations:

- For \(( f )\) expressed as \(( u(x, y) + iv(x, y) )\), where \(( z = x + iy )\), it must satisfy: \(\frac{\partial u}{\partial x} = \frac{\partial v}{\partial y}, \quad \frac{\partial u}{\partial y} = -\frac{\partial v}{\partial x}\)

Local Representation in Holomorphic Functions on Riemann Surfaces

- $D \subseteq X$ represents the neighborhood on the Riemann surface around point $x_0$.

- $\Delta \subseteq \mathbb{C}$ represents a disk in the complex plane.

- $\phi$ is the homeomorphism from $D$ to $\Delta$.

-

$f \circ \phi^{-1}$ maps from $\Delta$ back to $\mathbb{C}$, facilitating the analysis of $f$ as if it were defined in the complex plane.

- In the context of Riemann surfaces, local representation plays a pivotal role in understanding how complex functions can be analyzed and manipulated in settings that extend beyond the traditional complex plane. This concept is particularly valuable when dealing with the local properties of functions defined on complex manifolds like Riemann surfaces.

Conceptual Explanation

-

For any given point \(x_0\) on a Riemann surface \(X\), we can identify a neighborhood \(D\) around \(x_0\). This neighborhood can be mapped to a simpler, well-understood domain within the complex plane \(\mathbb{C}\), typically a unit disk \(\Delta\). This mapping is achieved through a homeomorphism \(\phi\), which translates the complexities of the surface’s local structure into the Euclidean domain of \(\mathbb{C}\).

-

The function \(f: D \rightarrow \mathbb{C}\) defined on \(X\) is then analyzed by considering its behavior when transported via \(\phi\) to \(\Delta\). This transposition allows for the application of established complex analysis techniques, as \(f\) can be treated similarly to functions directly defined on \(\mathbb{C}\).

The transformation of \(f\) through \(\phi\) and its subsequent analysis can be formally expressed as follows:

- Mapping Definition: The homeomorphism \(\phi: D \rightarrow \Delta\) maps the neighborhood \(D\) around \(x_0\) to a unit disk \(\Delta\) in the complex plane.

- Function Transformation: The function \(f\) is then considered in terms of \(\phi\), leading to the transformed function \(f \circ \phi^{-1}\), which operates within \(\Delta\).

This process is critical for determining if \(f\) is holomorphic at \(x_0\). Holomorphy is assessed by checking if \(f \circ \phi^{-1}\) meets the criteria for holomorphic functions within the complex domain of \(\Delta\).

Transition Maps and Holomorphicity Across Charts

Coordinate Charts and Their Role

Coordinate charts provide a methodological approach to treating Riemann surfaces as cohesive entities amenable to complex analysis. A coordinate chart on a Riemann surface $X$ is defined as a pair $(U, \phi)$ where $U$ is an open subset of $X$, and $\phi$ is a homeomorphism mapping $U$ onto an open subset of $\mathbb{C}$, typically visualized as a disk or similar construct.

This identification allows functions defined on the complex surface to be analyzed as if they were functions on the complex plane, greatly simplifying their study and manipulation under classical complex analysis techniques.

Preliminary Definition of Riemann Surfaces

Riemann surfaces can initially be described as surfaces covered by a collection of charts $(U, \phi)$, where each chart encapsulates a portion of the surface mapped homomorphically onto an open subset of $\mathbb{C}$. This setup highlights a potential complication: \(X = \bigcup_{\alpha \in I} U_{\alpha}\)

Where $I$ is an indexing set for the charts. The primary concern arises when defining holomorphic functions across these charts, particularly when a point $x_0$ appears in multiple overlapping charts. The definition of holomorphy must be consistent regardless of the chart, emphasizing the function’s intrinsic properties rather than its representation under any specific coordinate system.

By defining transition functions $g_{\alpha \beta} = \phi_\beta \circ \phi_\alpha^{-1}$ that are holomorphic, the structure ensures that holomorphicity is a consistent property across the entire surface, regardless of the local coordinate representation. This foundational aspect solidifies the concept of Riemann surfaces as true complex manifolds, where local complexities are globally harmonized through sophisticated mathematical frameworks.

Transition Maps

Transition maps are essential mechanisms within the framework of Riemann surfaces, ensuring that the manifold structure robustly supports complex analysis across its expanse. These maps are particularly critical when dealing with overlapping charts on the surface, such as $(U, \phi)$ and $(V, \psi)$. The transition map, denoted by $\psi \circ \phi^{-1}$, plays a pivotal role in maintaining the consistency of the complex structure:

\[\psi \circ \phi^{-1}: \phi(U \cap V) \rightarrow \psi(U \cap V)\]This mathematical requirement guarantees that the complex structure is preserved across different regions of the surface. It ensures that functions recognized as holomorphic within one chart exhibit the same properties in all overlapping charts, thereby upholding a uniform analytic structure across the surface.

Holomorphicity Across Charts

The holomorphy of functions on Riemann surfaces is deeply tied to their performance under these coordinate transformations. To qualify a function $f$ as holomorphic across a Riemann surface, it must show consistent holomorphic behavior under the transformation by each chart’s mapping. Specifically, if $f$ is holomorphic at a point $x_0$ in a chart $(U, \phi)$, then for any other chart $(V, \psi)$ that overlaps with $U$ at $x_0$, the function must be holomorphic when transformed by both mappings:

- $(f \circ \phi^{-1})$ must be holomorphic on $\phi(U \cap V)$

- $(f \circ \psi^{-1})$ must be holomorphic on $\psi(U \cap V)$

These conditions emphasize the integral nature of holomorphy as a characteristic that transcends local chart boundaries and becomes a global property of functions on Riemann surfaces. By ensuring that these transition maps and transformations maintain holomorphic integrity, Riemann surfaces facilitate a broader and more profound application of complex analysis, extending classical techniques into more complex topological structures.

Transition Function Definition:

The transition function is defined as: \(g*{12} = (\phi*{\alpha*1}^{-1} |*{U*1 \cap U_2}) \circ (\phi*{\alpha*2} |*{V\_{\alpha21}})\) This function maps from one local chart to another through the overlap of their respective domains, where \(( U_1 )\) and \(( U_2 )\) are overlapping subsets of charts \(( \alpha_1 )\) and \(( \alpha_2 )\).

Homeomorphism and Open Sets:

| Both components $$( (\phi_{\alpha_1}^{-1} | {U_1 \cap U_2}) )\(and\)( (\phi{\alpha_2} | {V{\alpha21}}) )$$ represent open subsets, ensuring the transition map functions as a homeomorphism. This is crucial for maintaining the integrity of the Riemann surface’s structure. |

Holomorphic Isomorphism:

To maintain the holomorphic nature of functions, the transition function \(( g_{12} )\) must not only be a homeomorphism but also a holomorphic isomorphism. This means it should preserve the complex structure, ensuring that the function is injective and remains holomorphic across the transition:

\[(f \circ \phi*{\alpha_1}^{-1}) \circ g*{12} = f \circ \phi\_{\alpha_2}^{-1}\]This equation demonstrates that the function \(( f )\) maintains its holomorphic properties across overlapping charts, effectively showing that the holomorphic nature of \(( f )\) is preserved through the mappings from one chart to another via the transition map.

Conclusions

In this introduction, we delved into the complex analysis of Riemann surfaces, starting from the basic definitions and moving towards more intricate properties of functions defined on these surfaces. By identifying and examining neighborhoods around specific points, such as $(X_0)$, we began to unravel the fundamental characteristics of holomorphic functions within these local environments. Additionally, we explored how coordinate charts serve as essential tools for translating the complex topological structure of Riemann surfaces into manageable subsets of the complex plane. These charts, while localized around neighborhoods, crucially link the local geometric properties to the broader analytical framework, allowing us to extend complex analysis techniques to the realm of Riemann surfaces effectively.

Final Thoughts

Riemann surfaces offer deep insights into complex functions, linking concepts across topology, geometry, and complex analysis, with promising applications in machine learning and deep learning. Their complex mappings and topological properties are analogous to the transformations seen in high-dimensional neural networks, providing inspiration for new algorithmic strategies and neural architectures.

For example, the holomorphic properties central to Riemann surfaces could influence the development of novel activation functions or optimization techniques in deep learning. Additionally, perspectives from projective geometry and geometric algebra enrich our approach to algorithm design, suggesting innovative ways to structure data and transformations in AI systems.